Jazz has always been a global language, connecting musicians and audiences across continents. In our recent interview on This Is Jazz, we had the pleasure of speaking with UK jazz drummer Alasdair Pennington. His insights into the UK jazz landscape, his creative process, and the realities of releasing independent music offer valuable perspectives for both music lovers and aspiring artists.

The UK Jazz Scene: Thriving Despite Challenges

When asked about the differences between the UK and US jazz scenes, Pennington offered a refreshingly honest perspective. While many American jazz musicians look enviously toward Europe, believing there’s deeper appreciation for jazz overseas, the reality is more nuanced.

“I have a lot of peers who themselves have to diversify to make a living,” Pennington explains. “The average working musician wherever in the world, it can be a pretty tough industry.”

The standard setup for jazz musicians in London, according to Pennington, involves juggling creative projects with bebop gigs around town, often supplemented by teaching. Despite these challenges, London’s jazz scene is undeniably vibrant, featuring legendary venues like Ronnie Scott’s and the 606 Club, alongside a robust network of concert halls and symphony venues that touring artists frequent.

Like many cultural centers, the UK jazz scene has a rich diversity of sub-genres that coexist harmoniously. From straight-ahead bebop to the rising Afrobeat-influenced South London sound, different musical pockets feed into each other, creating an amazing variety of expression for music lovers of all types.

Musical Influences: From Art Blakey to Brian Blade

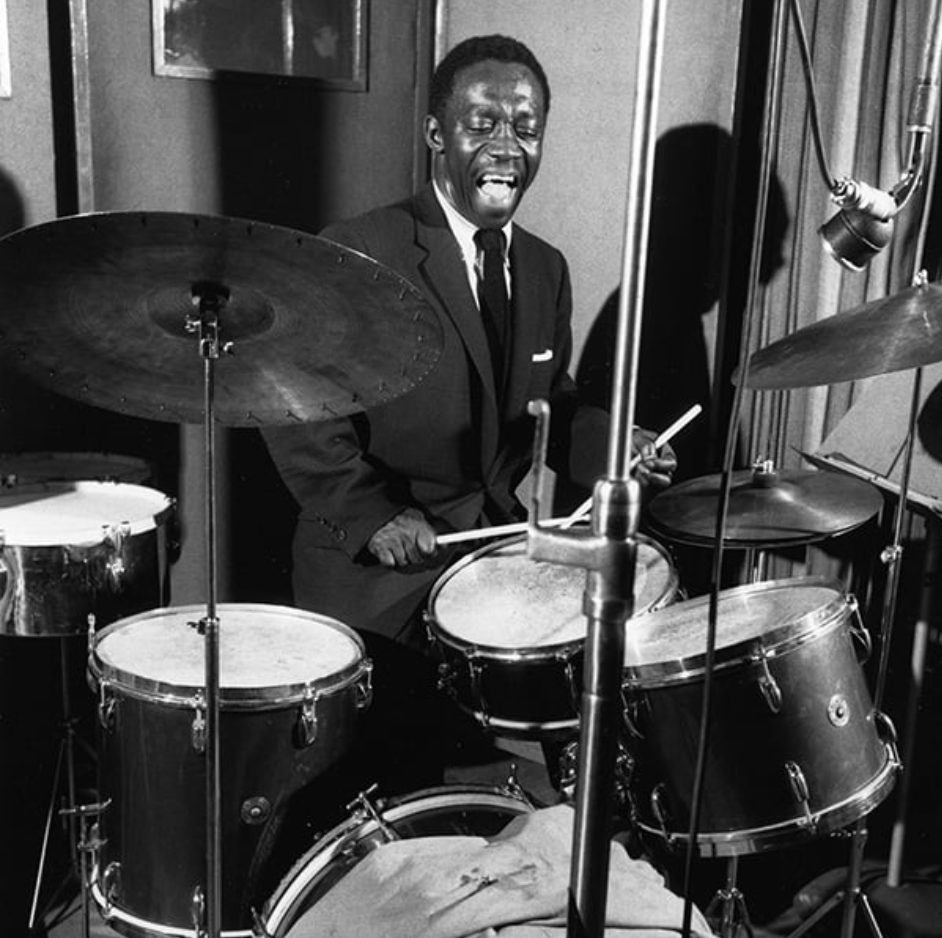

Alasdair Pennington’s musical journey began with the commanding presence of Art Blakey. “The first drummer I remember actively noticing when I was first listening to jazz records was Art Blakey,” he recalls. “I was just instantly drawn to his sound, his whole approach.”

His influences span generations, from pioneers like Kenny Clark and Philly Joe Jones to contemporary masters like Brian Blade, Bill Stewart, and Terri Lyne Carrington. Particularly formative was Wayne Shorter’s album “Allegria,” which featured both Brian Blade and Terri Lyne Carrington. “Before I really knew about Brian Blade and Terri Lyne Carrington, they were sort of already in my ears,” Pennington notes.

This connection to the music’s lineage while embracing contemporary voices reflects a broader theme in Pennington’s approach: respecting tradition while finding space for personal expression. This balance of tradition and innovation can be heard particularly in Pennington’s album, “This Is“.

The Art of Drumming and Composition

One of the most fascinating aspects of our conversation was exploring how a drummer approaches composition. As a non-tonal instrument player, Pennington’s process is unique: “I would say primarily when I’m writing, I use the piano.”

His compositional method involves finding “an idea or a sound or a concept” and developing it at the piano, backed by his understanding of traditional functional harmony. This approach is evident in his debut album “This Is,” where he skillfully balances written material with improvisational freedom.

Take his track “10 to 12,” for example. The piece features independent horn lines that weave together and apart, creating music where “you can’t tell, was this written out or is this improvised?” This effect is achieved by purposefully giving space to the horn players while providing strategic cues for ensemble moments.

The Reality of Independent Music Release

For aspiring artists, Pennington’s account of releasing his debut album offers invaluable insights into the modern music industry. The process, he discovered, is essentially two separate projects: creating the album and releasing it.

The creative phase involved finding an affordable London studio (Buffalo Recording Studios) that could capture both the classic “musicians in a room” interaction and the clean, produced sound of contemporary jazz releases. He emphasizes the importance of having proper engineering expertise while maintaining sight lines between musicians.

The release phase proved equally demanding: “It was a lot of me sat behind a computer sending emails and stuff.” From artwork and photography to distribution decisions and marketing strategy, the administrative side can feel overwhelming. However, as Pennington discovered, “before you do it, it just seems like an impossible task… once you’ve done it all, you’re ready to do it again.”

His partnership with Hidden Threads Records, an independent label run by his album collaborator Matt Anderson, exemplifies how personal connections can create opportunities. It’s a reminder that in the music world, relationships often matter as much as talent.

Lessons for the Jazz Community

Pennington’s journey offers several key takeaways for jazz musicians and music lovers:

For Musicians:

•Teaching* can be both financially sustaining and musically rewarding

•Collaboration and personal relationships are crucial for career development

•The administrative side of releasing music is substantial but manageable

• Balancing written material with improvisational space creates compelling music

For Music Lovers:

•Supporting artists through platforms like Bandcamp directly benefits independent musicians

•The UK jazz scene offers exciting diversity beyond traditional categories

•Contemporary jazz successfully bridges traditional approaches with modern production values

*for more on teaching jazz, checkout our book How to Teach Jazz & Improvisation

Connect with Alasdair Pennington:

•Website: alistairpennington.co.uk

•Instagram: @alasdairpennington

•Bandcamp: “This Is” available on all major streaming platforms

For the best way to support independent artists, Pennington recommends purchasing through Bandcamp, where you can find both digital downloads and physical CDs.

Sign up for our newsletter & get more interviews sent directly to you!

Interview Transcript

Quentin Walston (00:00)

to This Is Jazz. We have Alasdair Pennington here, amazing jazz drummer, composer, recording artist. So well, can you introduce yourself?

Alasdair Pennington (00:09)

Yeah, thanks a lot Quentin. Yeah, thanks for having me.

Pleasure to be here. Yeah, my name is Alasdair. I’m a jazz musician, drummer, composer from originally from Greater Manchester in the North of England. And I’m now based in London. Yeah, I’ve living here for a few years now. And yeah, I guess I’m primarily a session musician side person is kind of like

the majority of my work and kind of work mainly in the realms of jazz and improvised music. Yeah, so just, yeah, doing recording, gigging, musical things around London. And yeah, I’m sure one of the things we’ll come on to is I’m also band leader and composer and put out my first record at the end of last year, which was great. So yeah.

Thanks a lot.

Quentin Walston (01:10)

Congratulations

on

So what is the UK jazz scene like? Because I know we jazz musicians in the United States, almost when we hear about the European jazz scene, we hear that like people out there absolutely love jazz and we’re almost envious. Like, man, if only the European jazz sensibility was here in the United States, because I mean, in the United States, a lot of jazz musicians

have to diversify. They’re not always just playing jazz. They might have to take cover band or wedding band gigs and stuff like that just to fill out their schedule. Do you feel that the UK jazz scene has an active and deep appreciation for jazz?

Alasdair Pennington (01:54)

Yeah, I mean that’s

funny because actually in the UK and Europe a lot of people talk about like America, like jazz being their sort of equivalent classical music and there being this like deep cultural appreciation for it. Yeah, I would say, yeah, mean, yeah, the UK has a very fertile music scene, not just in jazz, but all sorts of

Quentin Walston (02:10)

Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Alasdair Pennington (02:24)

of genres really, yeah there’s lots of different pockets around the UK of great musical cities, London being a big one of them. Yeah, I mean I’d say yeah I have a lot of peers who yeah themselves have to diversify to make a living, I guess you know the average working musician wherever in the world it’s you know it can be a pretty tough industry and I guess yeah that

Quentin Walston (02:34)

Hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (02:54)

that is a common thing. I mean myself and a lot of my peers, the sort of standard jazz musicians set up in London around the UK I would say is you sort of do your own creative projects and you do the like, yeah, a lot of sort of like standard bebop type gigs around town. And then a lot of people myself included do teaching on the side and yeah, find that.

find that very rewarding and also sort of is basically a part of their practice, you know, as a musician. But I would say, yeah, like there’s a very happening scene here in London. There’s, yeah, you have like the infamous clubs and places like Ronnie Scott’s and yeah, the 606 Club. also, you know, in the UK you have this big like classical music.

Quentin Walston (03:25)

Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Mm-hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (03:52)

scene with a lot of sort of concert halls and symphony halls. So there’s a sort of big circuit and you know lots of venues that people play at, particularly like touring artists will come and play at those venues. So yeah it’s cool, there’s definitely a lot happening and then yeah I mean it’s kind of gotten harder in the UK since Brexit happened to

Quentin Walston (03:55)

Hmm.

Yeah.

That’s great. Yeah.

Alasdair Pennington (04:22)

work and yeah play music in Europe but yeah it’s yeah I mean Europe equally has a very thriving jazz scene and yeah I’ve done some work in places like Germany and Austria and Slovenia so there are opportunities yeah to play abroad and actually a lot of people in London are like European musicians who’ve come and started working here so

Quentin Walston (04:29)

Right.

Mm-hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (04:51)

Yeah, there’s definitely sort of like cross cross-pollination between places in Europe. Yeah.

Quentin Walston (04:55)

Cool. Yeah.

it was interesting. mean, you brought up the with the US our history definitely has such a rich jazz heritage and it is in many ways our classical music. It’s tough. to find it remain seen that way in popular culture.

which I guess it kind of gets into the diversification that I was talking about. But also I found over here the sound that jazz artists go after has to be diversified a lot as well. One of the things that I love about your sound is it’s more of the straight ahead sound, the straight ahead swing sound. I found.

In the U.S. it really depends on what city you go to if they’re gonna have a straight ahead or like a bebop approach or something that’s more like hyper modern or avant-garde or hip hop influenced. But it sounds like you said in the UK a lot of kind of bebop or straight ahead jazz seems to be the dominating style, what would you say?

Alasdair Pennington (06:04)

I would say that’s

definitely prevalent I think. Yeah, I mean the kind of the nice thing about London and the UK actually is that you have a lot of different sort of sub-genres and they all coexist quite nicely. But I would say, yeah, I would say there’s definitely that like a contingent of musicians who are sort of like…

Quentin Walston (06:24)

Mm-hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (06:34)

Yeah, inspired by that sort of 50s, 60s bebop sound and either A, try to emulate that or A, like B, trying to sort of take that and then have that as a basis for their contemporary sound. But I would say, I mean, in London, there’s been a rise in sort of…

Quentin Walston (06:42)

Mm-hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (07:03)

this sort of like Afrobeat thing, like South London musicians. This, yeah, sort of like beat inspired thing. And yeah, actually that’s that’s kind of one of the nice things because all these different pockets sort of coexist and feed into each other. But there’s yeah, there’s definitely places around town where, yeah, people go and they want to hear like straight ahead.

Quentin Walston (07:16)

Yeah.

Alasdair Pennington (07:32)

swing playing,

Quentin Walston (07:33)

I think that would be a good pivot to talk about your music and your development specifically I was looking at your bio and you listed I mean some of the the absolute greats I Love reading about those you listed Jimmy Cobb. I love Jimmy Cobb, man He did just the way he he’s like always he pushes like he’s right on top of the beat, but he’s not like Making the tune go faster. Like he has this amazing way of like keeping

Alasdair Pennington (07:42)

Hmm.

Yeah.

Quentin Walston (08:02)

keeping it going, but anyway, I’m getting ahead of myself. So when you look at your development, what are some of your favorite players as you kind of found your voice as a jazz musician?

Alasdair Pennington (08:11)

Yeah, mean,

yeah, definitely Jimmy Cobb would be big one. The first kind of drummer I remember actively noticing when I was first listening to jazz records was Art Blakey. I think I listened to maybe like a greatest hits Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers album.

And yeah, it was just instantly drawn to his sound, his whole approach. So yeah, he was a big one. And then, yeah, I mean, as I sort of developed and started, you know, understanding the music and lineage more, I started listening to the great pioneers like Kenny Clark, Philly Joe Jones. Yeah, all those cats.

And yet like listening to them, appreciating them. then as I went to music college, like actually, you know, starting to transcribe and dig deep into that, to their work. So definitely, you know, that, that fifties, sixties, great American, black American music periods. And then I guess like, yeah, more contemporary. I’m really influenced by Brian Blade’s, amazing player.

Bill Stewart, Kenny Washington, Terry Lynn Carrington, another great musician. There was actually an album that I used to listen to, I think it was my parents’ record and they just had it on quite a lot, a Wayne Shorter album called Allegria. It’s kind of, yeah, I think it’s kind of like a lesser known one, but it’s like that footprints quartet with Brian Blade and Pati tucci and Danillo Perez.

Quentin Walston (09:32)

Hmm.

Yeah.

Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (10:00)

But Terry Lynn Carrington also plays on that album. So before I really knew about Brian Blade and Terry Lynn Carrington, they were sort of already in my ears. So I was influenced by those cats.

Quentin Walston (10:01)

Yeah.

you

Yeah.

I got to see Wayne Shorter a few times and yeah, just seeing Brian Blade and his immediate dynamic contrast just would blow my mind. Cause he’s just like keeping it going and then suddenly this big bomb just erupts out of nowhere and I just, I absolutely love it. So that’s so cool and such great communication. And I feel like

Alasdair Pennington (10:24)

Hmm

Yeah.

Quentin Walston (10:42)

You mentioned some of the really early guys like Philly Joe Jones and you can correct me if I’m wrong or talk about it. It feels like with the early guys there was some communication but it was a little more subtle. was like their main thing was timekeeping. They might do a little bit of answering on the snare but I feel like as drums progressed through the late 50s into the 60s they seemed to be more communicative.

the later we get where drummers are really interacting rhythmically and dynamically. Do you feel the same or am I off on that?

Alasdair Pennington (11:16)

Yeah, think broadly, yeah,

that, yeah, that probably sounds about right. Yeah, I’m just thinking, I mean, like people like Art Blakey and Kenny Clark and Jimmy Cobb definitely, I mean, the reason that they, I think, appealed to me as I was just sort of getting into that way of playing the instrument was that sort of like, that very refined simplicity almost of their…

Quentin Walston (11:40)

Mm-hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (11:42)

they’re playing, know, mean, like Art Blakey is a great example of that. You know, he can drive a band and he’s not really, yeah, there’s not much interaction from him in terms of like comping on the snare and bass drum. It’s just like this driving shuffle or driving swing. And then when it gets to his solo, it’s like, that’s when he lets everything out. And I would say, yeah, similar thing about Kenny Clark, you know, it’s sort of like this, it’s more like an accompanist.

Quentin Walston (11:45)

Mmm.

Hmm.

Mm-hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (12:13)

role, not to say that they’re not communicating, but yeah I think you’re probably right to say that it’s like yeah more subtle. I mean I guess like as you listen to Philly Joe Jones as he sort of yeah like the later in his career I would probably argue that there was yeah more he’s yeah there’s sort of more going on there ⁓ but yeah I would say that’s probably largely

Quentin Walston (12:16)

Mm-hmm.

Mm.

As far as when you’re a band leader, since you’re not a tonal instrument, what is your compositional process when you’re writing melody or you’re writing a chart and then you’re thinking about your role?

in that, like, what is your process like when you’re writing? Because you just did what, is it a 10 or eight track

Alasdair Pennington (12:58)

Yeah,

Quentin Walston (12:59)

It was a nice full album.

Alasdair Pennington (12:59)

like six or seven tracks, I think.

Yeah. But yeah, I mean, like one of them is like 13 minutes long or something. But yeah, mean, I’m definitely, yeah, first and foremost, a drummer. mean, I have played other instruments, but I’m not, I mean, I have some peers and friends who are just like, you know, incredible piano players and drummers and they, you know, they could

Quentin Walston (13:05)

Mmm, yeah.

Mm.

Alasdair Pennington (13:25)

gig on either. But yeah, I mean, I would say primarily when I’m writing, I use the piano, but I’m definitely not a piano player. I guess because I’ve studied and understand like the theory and harmony of it, that’s kind of like the easiest way to just see everything. Sometimes ideas and

Quentin Walston (13:26)

do it.

Mm.

Mm-hmm.

Mm.

Alasdair Pennington (13:50)

like little beat solo riffs will come and will be the basis of a tune from the drums from my instrument but largely I would say that my compositional process is like just finding sort of an idea or a sound or a concept and usually just sort of playing around with that on the piano and then yeah I like to sort of flesh that out

Quentin Walston (14:01)

Mm.

Mmm.

Alasdair Pennington (14:17)

as

much as possible and then sort of back that up with my understanding of traditional functional harmony to sort of put it into the structure of a composition.

Quentin Walston (14:30)

on your tune, is it 10 to 12, I really liked the, there’s a lot of like independent horn lines that kind of then will come together and then they’ll come apart again. Were you writing contrapuntally or what was your approach to those horn lines or is it kind of giving them room to just improvise like, hey, we’re gonna be playing whatever we want and then we’re gonna come together on this main melody or?

Alasdair Pennington (14:31)

Mmm.

Hmm. Yeah,

sure. Yeah. So 10 to 12. I think a lot of the times where the horns are overlapping, that’s, yeah, they’re just like given the space to do that in the music. And then basically the chart for that is like, it’s open to start with. It starts with just like a…

Quentin Walston (14:58)

Can you break that tune down for me, I guess?

Mmm

Alasdair Pennington (15:18)

rhythm section playing changes or playing just time really and then the horns kind of have chance to play around after this like opening melodic figure and then I cue the main melody and then after that it goes back to having a bit more freedom again so it’s kind of like I guess I’m kind of like purposely giving

Quentin Walston (15:21)

Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Alasdair Pennington (15:44)

space to the home players. I mean I was kind of you know writing with those musicians in mind sort of or arranging with those musicians in mind so it’s like yeah it’s like a combination of having the material but also just like allowing the players space to do what they do best you know.

Quentin Walston (15:48)

Yeah.

Yeah.

I absolutely love that. when it’s like blurring the lines when you can’t tell like, was this written out or is this improvised? So yeah, so well done. And yeah, I mean, you can really only achieve that when you have players that you really trust and you really know their voice on their instruments. So you can kind of have an idea of who you’re writing for, but really, really cool. Did you find that?

Alasdair Pennington (16:05)

Hmm.

Yeah, definitely.

Quentin Walston (16:27)

A lot of the tracks kind of followed that template where you have a general idea and you’re kind of giving freedom to the player in the session.

Alasdair Pennington (16:35)

Yeah, I think

yeah, mean, some of those compositions actually wrote quite a while before going to recording them. So I sort of had a preconceived idea. But I think like in this style of music, there’s a point where you sort of have to, you know, let go to some extent, you know, like you ultimately, you know, the style of music we’re writing for, it’s like…

where we want to give space to the musicians to improvise because that’s what they’re trained to do and it’s like in this style of music that’s kind of like you know that’s that’s it really isn’t it you know so it’s like I guess yeah they probably all follow a similar tempo where I like I have specific desires about what

what I want the vibe to be or the sound to be and things that I specifically want are written out quite specifically but I would say that a lot of that music is also, there’s definitely a lot of room in there for the band to interact.

Quentin Walston (17:50)

Can you tell me, I can’t remember, was this an entirely indie album? Did you work with a label? What was the process for this one?

Alasdair Pennington (17:58)

Yeah, it

kind of a bit of both. It was released on an album called Hidden Threads Records, which is a small independent label based here in London. And it was set up by a friend of mine who actually played on the album, Matt Anderson, the tenor saxophone player. So that was a nice fit.

Quentin Walston (18:16)

Hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (18:23)

I was recording, recorded the music in like summer of 2022 and then I was kind of sat on it for a while and working out what to do next with it, you know, the process of releasing it and sort of working out what route I wanted to take. And yeah, I was just talking to Matt and he, yeah, kindly offered that, yeah, he’d set this label up.

Quentin Walston (18:35)

Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Yeah.

Alasdair Pennington (18:51)

a years prior. And yeah, he offered the chance to release it on that. So it’s, it’s, you know, it’s, it’s not a huge jazz label. It’s just run by Matt. This, he doesn’t have a team of others behind him. So everything is through him. But yeah, I guess it’s a kind of a combination of like a label, but it’s, you know, it’s done independently. But I would say what was really useful was just like having

Quentin Walston (18:57)

Excellent.

Mm-hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (19:22)

the expertise and advice that someone had done that before. Because releasing music independently, there’s a lot of holes you have to, loops you have to jump through. So yeah, it’s independently but through an independent label.

Quentin Walston (19:31)

Yeah.

Mm-hmm.

That’s great. Yeah, I’ve released all of my projects independently and there are a lot of hoops to jump through. part of our audience is aspiring artists or artists at various parts in their career. And a lot of people don’t know what goes into writing an album. They feel that it’s something they have to do, right? If you’re a musician, need to create music.

Alasdair Pennington (19:46)

Yeah.

Hmm.

Quentin Walston (20:10)

But yeah, can you walk us through what is the process of creating an album? Let’s say you have tunes. Like, all right, I got these cool tunes that I wrote and I got some people that I know can play them really well. How do you get from, I’ve got tunes to now your tunes are on Spotify. What was that process like for you?

Alasdair Pennington (20:31)

Yeah, sure. Yeah, I mean, guess that’s like,

it’s funny because it’s like that’s there’s a lot of stuff in between those two things. But, you know, yeah, to like the general public that just like it just happens, you know. Yeah, I mean. So, I mean, yeah, I guess for me, a big, big thing was just like firstly finding the space to record it. I mean, luckily in London, there’s yeah, there’s a lot of great

Quentin Walston (20:41)

Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (20:59)

recording studios available. I mean, you know, for me as an independent artist, I got some funding, but that was really for like the sort of promotion and release of the album rather than the recording of it. So, yeah, the actual like setting up of the recording, I had to sort of fund and get that going myself. So, yeah, just like practically was finding a space that was

Quentin Walston (21:18)

Mm-hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (21:29)

you know, not extortionately expensive. And also, yeah, that would have that, be able to have that approach of recording a contemporary jazz album because I really wanted to have that mix between, you know, like the classic jazz albums where it’s just some musicians in a room and it’s, you know, capturing that interaction, but also like the, like the sort of…

Quentin Walston (21:35)

Yeah.

Mm-hmm.

Alasdair Pennington (21:57)

more contemporary, you know, like the records are coming out on Blue Note now, for example, you know, it’s a much more clean and sort of produced sound, which I also really like, you know, it’s, I mean, I guess, yeah, it’s just like advancements in recording technology,

Quentin Walston (22:05)

Mm-hmm.

Did you all use a traditional studio or did I ask is I mean an album now like you mentioned like the early albums there, they’re in a room and people if they want they can buy some microphones they can spend $1,000 or something buy some microphones by interface and set up a mobile studio or did or and then there’s you know the opposite end where these huge studios that you’re just

Alasdair Pennington (22:25)

Mm.

Okay.

Quentin Walston (22:41)

paying thousands of dollars or

thousands of pounds just a day to be in there, like, what was that for you?

Alasdair Pennington (22:44)

Yeah, I I think I wanted

to do it in a studio just to have, yeah, just like to have the expertise of an engineer and just like to have a proper session recorded, you know, and like I wanted the music to be, I wanted the performances to be captured well, you know, and properly by, it was definitely a balance of also wanting to sort of capture that vibe of, yeah, just like,

Musicians being in a room and interacting I didn’t want it to be like everyone was in their own booth and there was no sight lines, you know So yeah in the end I recorded at this place Buffalo recording studios, which yeah is a studio here in London And yeah, it was it was a great balance. We had a really good engineer And then yeah, I got it got the audio mixed and mastered by Yeah mixed by a friend of mine and then mastered by

⁓ someone in the States actually that I kind of knew of, ⁓ but yeah, just, sent the files to him, which is cool. So, yeah, after like the, having the finished audio product, I was, I was kind of sat on it for a while, just working out. Yeah. Like what, what the next step was, because, ⁓ in terms of like getting out into the world, there’s sort of a lot to think about, you know, like from the visuals of like.

Do you want artwork? Do you want photography? know, like having someone to design all that. then, you know, thinking about the release, like, you know, like is physical releases, is that a worthwhile endeavor or should it just be a digital thing? You know, so I eventually, yeah, I eventually sort of after thinking about it sitting with it, I sort of…

had a visual in my mind that I wanted. And yeah, that was then at the same time talking to Matt, the founder of Hidden Threads Records. And yeah, it sort of all came together very naturally actually and very nicely. And it was a nice, a really nice fit releasing the music on Matt’s record, my record label, it’s my first release as leader and Matt played on the album. And it’s just…

you know, sound of the thing was sort of matched the record in terms of the other music that was on the label. So yeah, I mean, it was a lot of admin as well, know, just like getting on that stuff done, reaching out to people. So was, yeah, a lot of me sat behind a computer sending emails and stuff.

Quentin Walston (25:25)

Yeah.

It’s so much.

Alasdair Pennington (25:43)

Yeah, it’s one of those things that’s like, before you do it, it just seems like an impossible, I mean, yeah, you’ll know, it just seems like an impossible task of like, how am going to accomplish all these things? then, as you, once you’ve done it all, it’s, yeah, I was sort of thinking like, okay, well, I’m ready to do it again, you know. Yeah, let’s do the next one, yeah.

Quentin Walston (25:43)

Mm-hmm. Yeah.

Yeah, yeah, absolutely. It it feels to me like an album is is two separate projects, like there’s the there’s the creative side, like, OK, I’m going to create an album and it’s writing the music and rehearsing it and getting the band together and getting in the studio and playing and mixing and mastering it. And that’s the creating an album. But then after you’re done with that.

Then the whole new project, the second project starts, which is like, you know, releasing the album. Yeah. Like who am I going to release it under? I need artwork. Is it formatted right? I need to put it up with my distributor. Am I set up with all the different royalties organizations and all of that? And, ⁓ and then, do I market it on social media? Do I use paid advertising? It’s, it’s, it’s a lot. and I think that

Alasdair Pennington (26:36)

Yeah. Yeah.

That’s it, yeah.

Quentin Walston (27:03)

There’s a lot of research that artists can do, but yeah, until you really do it, you don’t understand quite the weight of that project. But that’s cool that you’re excited to do some more.

Alasdair Pennington (27:08)

Yeah.

Yeah.

Quentin Walston (27:15)

where can we find your album is called This Is, correct?

Alasdair Pennington (27:17)

This is, yeah, yeah, it’s on,

people can go to my website, which is alistairpennington.co.uk. They can, yeah, I’m selling CDs and the album on my Bandcamp page. If you go to my Bandcamp, just search my name. Yeah, I mean, that’s the best place if you want to support independent artists, I guess. Yeah, it’s available on all usual places, but…

Yeah, Band Camp is where you can get the CD.

Quentin Walston (27:47)

on social media?

Alasdair Pennington (27:46)

yeah, Instagram

is my name. Alasdair Pennington. It’s A-L-A-S-D-A-I-R Pennington. that’s the main social media for me. I’m on like Facebook as well. Same thing, Alasdair Pennington, but yeah, mainly Instagram.

Quentin Walston (28:03)

All right, well thank you so much Alasdair. We really appreciate you coming on. This is Jazz and yeah, thanks again.

Alasdair Pennington (28:08)

Thanks Quentin for having me. Pleasure to

contribute. Thank you.